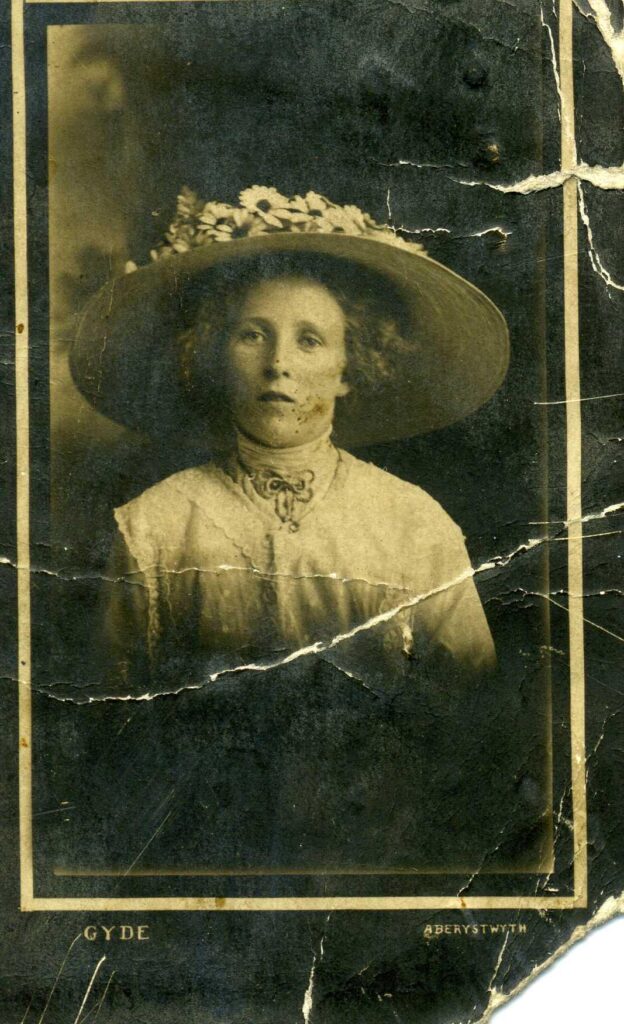

Aunt Mary Jones

Aunt Mary Jones

How do you learn about an ancestor who didn’t leave behind a journal? Many people want to understand their heritage but think they need a written record from their ancestors to know their family history. We will leave to our descendants our social media updates and selfies. But what have our ancestors left for us to discover about them?

Throughout our ancestors’ lives, governments, religious groups, and other institutions created records about our ancestors’ births, marriages, deaths, and many other life events. These records combined with historical context (or research about the time and place the ancestor lived) give us a good idea about what life was like for an ancestor.

For example, everything I learned about my Welsh ancestors came from studying historic records and Welsh history. Here is what I’ve discovered about my fifth-great-grandmother, Mary Rowland:

-

She was born in the 1790s and was the daughter of a stonemason.

-

She couldn’t read and drew an X as her signature on her marriage record.

-

She had five children with her husband John Jones, and he died when she was forty years old and their youngest child was only three years old.

-

She and her family attended the Calvinistic Methodist church, a church that was born out of the Welsh Methodist revival and separated from the Church of England. In the indexes, the church is listed as “nonconformist.” The chapels were the heart of the community. The church had a strong tradition of hymn singing. Singing is a part of the Welsh heritage. My great-grandmother used to tell me stories of her Welsh father going about the chores on his farm while singing Welsh hymns.

-

By 1841, Mary remarried a farmer named Griffith Roberts, and they had one daughter together. Griffith Roberts had about fifty acres of land and was most likely a sheep farmer or an oat farmer because the climate and soil conditions were not suitable for growing crops other than oats and the region has an ancient tradition of sheep farming. On the censuses, Mary’s occupation is listed as “farmer’s wife,” which I’m sure was a demanding job.

-

She lived in an ancient house named Cae’r Sais, which is an important archeological site in Wales with Bronze-age stone circles.